Redefining The “Public” Sector?

Or maybe I should title this “When Public Sector Isn’t ‘Public’ At All.” In recent blog posts, I’ve written about how “cities” are not just those formed around a city hall, headed by a mayor or city council, and run by civil servants. Universities, company towns, and even amusement parks are launching innovative technology-based initiatives to address issues around transportation, public safety, administration, and even healthcare and education. However, it seems that many of the new cities being created as “smart cities” are even themselves not really cities as we know them (that’s a lot of “cities” in one sentence). Are they perhaps redefining the public sector altogether?

Humor me as I ruminate on the definition of public sector. I usually think of the public sector as that which is government-owned, run by civil servants, and ultimately headed by an elected, appointed (or possibly a self-appointed) leader acting in the interests of the public or his/her constituency. Traditionally, at the core of a city is a public sector with many of these characteristics, with a mandate to provide basic infrastructure and services for the “public,” known in economic parlance as “public goods.” But, what if the city government itself is a private entity?

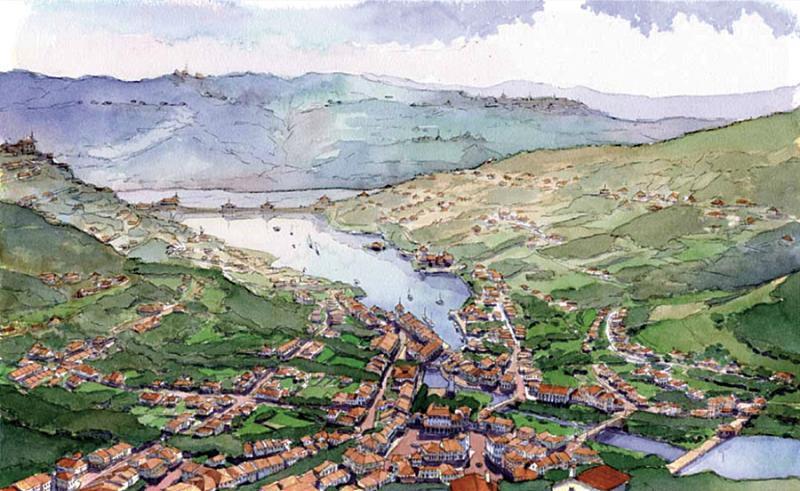

Lavasa, a new, planned city between Mumbai and Pune, is a corporation – Lavasa Corporation Limited, a Hindustan Construction Company (HCC) Group company. There is no public sector at its core. The corporation itself decides the priorities for the city and owns the goods and services it delivers, making them “private goods.” We’ve seen this model with toll roads, where the public pays to use the service provided by the private roads. However, on the scale of a whole city, this concept is relatively new.

Lavasa, a new, planned city between Mumbai and Pune, is a corporation – Lavasa Corporation Limited, a Hindustan Construction Company (HCC) Group company. There is no public sector at its core. The corporation itself decides the priorities for the city and owns the goods and services it delivers, making them “private goods.” We’ve seen this model with toll roads, where the public pays to use the service provided by the private roads. However, on the scale of a whole city, this concept is relatively new.

I recently spoke to the VP of Information Systems at Lavasa about the development of the city. He confirmed that it is run as a business:

- Lavasa Corporation belongs to private equity investors – Wipro and Cisco being two investors, in addition to the parent holding group HCC.

- Lavasa Corporation plans and manages all aspects of the city with a few exceptions: law and order, and other specific official administrative services such as issuing birth certificates or marriage licenses.

- Lavasa Corporation manages most other traditionally public sector services: transportation, parking, garbage collection, business registration, and even revenue sharing with local businesses (like the equivalent of local business tax collection).

- Lavasa Corporation issues RFPs for businesses and other services based on the overall plans for the city. Accor was recently selected to build and manage four hotels in the city. Relationships with these businesses are defined by a “special purpose vehicle” or contract that outlines the specifics of the revenue sharing agreements.

The only way Lavasa will be “public” is if it held an IPO – an initial public offering of equity in the company – becoming a public company. And, in fact, Lavasa’s IPO is in the works, having been filed with the Security and Exchange Board of India just a few weeks ago. But isn’t a city that is a public company really still just a private city?

The model has supporters in India and elsewhere. A $90 billion government-led project to develop the Delhi – Mumbai corridor includes plans to create five new cities by 2015. Although the project is government led, the cities will be corporations with private investors, with the Indian government maintaining only a minority share.

Paul Romer, an economist at Stanford, has written about what he calls “charter cities” similar to charter schools. These “cities” draft a charter or the premise or vision on which the city is to be built. Then investors and residents chose to participate – by “voting with their feet” (and wallets). These “charter cities,” Romer suggests, provide special zones which encourage foreign investment in places that might not have traditionally attracted that investment. Not everyone agrees, and many point to Brasilia as a monument to a planned city that never really happened – but wasn't Brasilia built by the government? The ideal of building a city persists, however. With the growth of urban population and the rise of new smart cities, the time might be right for a new model.

Paul Romer, an economist at Stanford, has written about what he calls “charter cities” similar to charter schools. These “cities” draft a charter or the premise or vision on which the city is to be built. Then investors and residents chose to participate – by “voting with their feet” (and wallets). These “charter cities,” Romer suggests, provide special zones which encourage foreign investment in places that might not have traditionally attracted that investment. Not everyone agrees, and many point to Brasilia as a monument to a planned city that never really happened – but wasn't Brasilia built by the government? The ideal of building a city persists, however. With the growth of urban population and the rise of new smart cities, the time might be right for a new model.

What does this mean for vendor strategists? It means that targeting the public sector doesn’t mean the same things it used to. These new cities are not just new population centers, built up organically. They are purpose-built, planned developments. But, more importantly, the stakeholders are different. And, business drivers are truly business drivers. Understanding the customer is key. Vendor strategists must understand the new public sector.