Windows Azure Crosses Over To IaaS

At its Professional Developers Conference this week, Microsoft made the long-awaited debut of its Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) solution, under the guise of the “VM-role” putting the service in direct competition with Amazon Web Services’ Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) and other IaaS competitors. But before you paint its offering as a "me too," (and yes, there is plenty of fast-follower behavior in today’s announcements), this move is a differentiator for Microsoft as much of its platform as a service (PaaS) value carries down to this new role, resulting in more of a blended offering that may be a better fit with many modern applications.

First off, it’s not a raw VM you can put just anything into. As of its tech preview, opening up later this year, it will only host applications running on two versions of Windows Server — no Linux or other operating systems. . . yet. Second much of the PaaS services on Azure span PaaS and IaaS deployments letting you easily mix VM role and Worker role components in the same service; sharing the same network configuration, shared components, caching, messaging, and network storage repositories. Third, Microsoft is also debuting, in preview, the ability to host virtualized application images in its Worker Role, another deployment option that can accommodate even more applications and components that previously were not a fit on the Azure platform. And SQL Azure Data Sync replicates and synchronizes on-premise SQL Server databases to Azure. All these moves give traditional Windows developers significantly higher degrees of freedom to try and then deploy to the Azure platform. If you have held back on trying Azure because you didn’t feel like writing your entire application on the Azure platform now the bar is a bit lower — assuming everything you write runs on Windows.

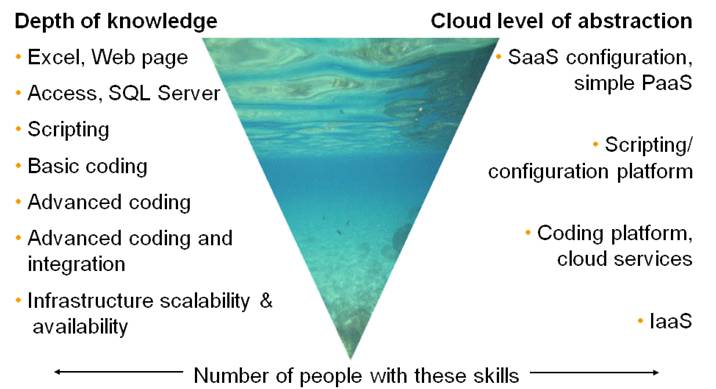

One could argue that these moves are really a "so what" given that nearly every public IaaS cloud delivers these same degrees of freedom — more frankly, since any app running on any OS can be deployed to a VM-based cloud. But we forget that there is a deeper level of developer skill required to leverage IaaS (see figure below). If your developer skills center around building applications in .Net, Java, PHP, Ruby or other languages and not down to the layer below, installing, configuring, and managing the middleware and operating system, IaaS is a steep learning curve. And frankly having to manage these lower layers cuts into go-to-market productivity. That’s always been the appeal of PaaS offerings. But PaaS carries two significant downsides which have kept its adoption lower than IaaS in our ForrSight surveys: fear of lock-in due to the abstracted middleware services and the difficulty in migrating on-premise code to the platform.

Neither fear is as real as it sounds, by the way. PaaS lock-in really isn’t that different than the old Java app server wars. WebLogic and WebSphere both supported the Java standard and you could port your app back and forth unless you tapped into their value added services. The same is true on most PaaS platforms. If you value the added services you will use them; and you will be locked in.

The truth about PaaS platform migration isn’t as daunting either. Most PaaS cloud services support one or multiple programming frameworks and adhere to the usual standards. How certain services are provided is usually where the work resides, not in the core functions of your application.

Much of the rest of Microsoft’s Azure were either catch up responses to EC2 announcements — extra small instances, dynamic, and secure caching — or enhancements to help Visual Studio developers and System Center administrators familiarity with Azure — Team Foundation integration, better reporting and management capabilities. Both are strong motives yielding good results. Microsoft’s culture is that of a fast follower but one with a strong listening engine and customer retention priority. As a result it mostly takes others’ ideas, enhances them for its installed base and innovates where it sees unique crossover opportunities between these aims. Usually the outcomes are easier to use and more enterprise-ready solutions.

Perhaps the most interesting of these cross-overs is DataMarket. The former Project Dallas is a "me too" of AWS’ Public Data Sets but one that is significantly easier to use and comes with a commercialization component for information providers that has no match among the cloud competitors. I’ll blog about this next.