Bringing The Public Back Into Public Safety Through Citizen Engagement

For some reason public safety has been a hot topic for me of late. I recently presented at ZTE’s Public Safety Summit in Dubai, where there was an audience of public safety officials and telecommunications ministry representatives from the Middle East and Africa. One element of the presentation that sparked interest and audience questions was citizen engagement.

We often think of public safety in terms of emergency services – police, fire, and ambulance; and, for many people, public safety first conjures up images of the police chasing bad guys – likely the effect of too many TV shows like Cops or Southland. But as I defined it in a previous blog, public safety covers a broad range of issues that touch a city’s inhabitants: crime prevention, traffic control, health services, public infrastructure management, and any of a list of emergency services including those for natural disasters such as earthquakes and flooding or incidents like urban wildlife sightings as well as fire or riots.

We often think of public safety in terms of emergency services – police, fire, and ambulance; and, for many people, public safety first conjures up images of the police chasing bad guys – likely the effect of too many TV shows like Cops or Southland. But as I defined it in a previous blog, public safety covers a broad range of issues that touch a city’s inhabitants: crime prevention, traffic control, health services, public infrastructure management, and any of a list of emergency services including those for natural disasters such as earthquakes and flooding or incidents like urban wildlife sightings as well as fire or riots.

In order to better act as the eyes and ears of the city – particularly given the mandate of doing more with less – many public safety organizations are returning to a kind of community policing – through better engagement with citizens. This isn’t a new concept.

“. . . the police are the public and the public are the police; the police are the only members of the public who are paid to give full-time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interest of community welfare.” – Sir Robert Peel, 1829

However, technology has provided new tools of engagement. These new tools provide mechanisms to better communicate, such as through Twitter or web-based video chat, as well as mechanisms to engage citizens in public safety activities. Here are a few examples:

The Philadelphia Police have been active on Twitter (@phillypolice) since September of 2009 and have more than 10,000 followers. According to the police, it’s been a great way to respond to people's questions, to give information to highlight programs that the police department is doing, and to highlight good works and police successes.

As the police officer behind the Twitter account noted:

"I'm not really doing anything more than what people did back in the '50s or '60s, people went out on foot patrol, they went into stores, they went and talked to people. I'm doing the same thing; I'm just doing it with my cell phone.” – Joe Murray @ppdjoemurray

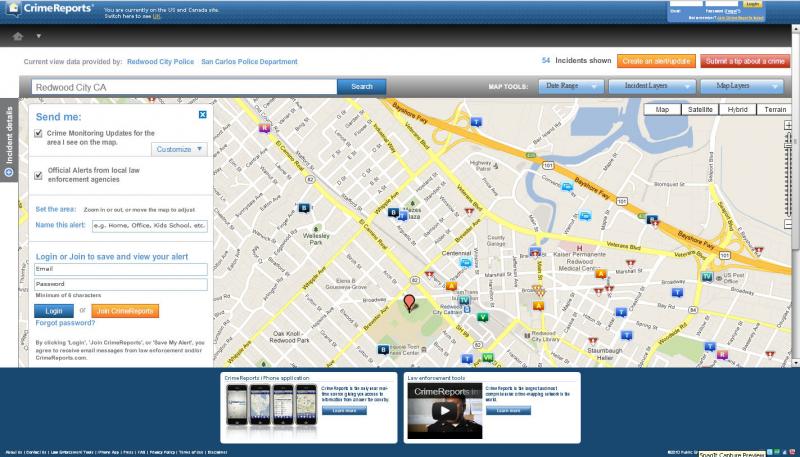

In another example, the Redwood City Police use various mechanisms for engaging citizens. One is video chat, which is available when officers are in the office. Unfortunately, there wasn’t an officer on the chat when I checked their website – but I like the idea of being able to chat with an officer. They also use Crime Reports, which is a crime mapping network with member police departments worldwide. Crime Reports provides mobile and web interfaces (see below) to allow citizens to report crimes, get automatic updates on geographical areas, or official alerts from specific agencies – clearly a technology-based community policing effort.

In another example, the Redwood City Police use various mechanisms for engaging citizens. One is video chat, which is available when officers are in the office. Unfortunately, there wasn’t an officer on the chat when I checked their website – but I like the idea of being able to chat with an officer. They also use Crime Reports, which is a crime mapping network with member police departments worldwide. Crime Reports provides mobile and web interfaces (see below) to allow citizens to report crimes, get automatic updates on geographical areas, or official alerts from specific agencies – clearly a technology-based community policing effort.

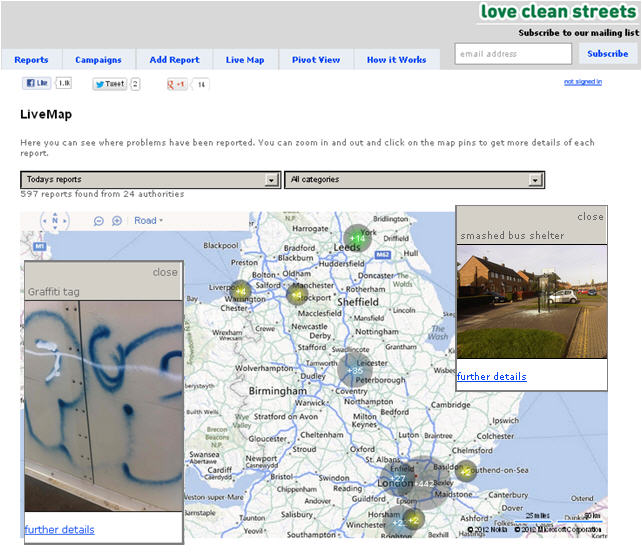

Other examples of citizen engagement are the tools available for reporting non-emergency incidents. According to the “broken window” theory, there is a correlation between the condition of a neighborhood and crime: The more broken windows, the more crime there will be. Although highly controversial, New York and other cities embraced the theory and focused on cleaning up neighborhoods. Recent census data on housing in New York appears to have confirmed the correlation. And, new citizen reporting tools bring citizens into the process of “policing” the conditions of their neighborhoods. City Sourced, SeeClickFix, LoveCleanStreets (see below), HeyGov!, and others provide these platforms. Not only can citizens report incidents, but they can also track progress on how their cities have responded to the reports.

Finally in one of my favorite engagement examples, Code for America fellows have developed applications for cities to engage citizens to actually do something rather than merely reporting. A Code for America fellow working with the City of Boston developed an application for people to Adopt-A-Hydrant during the winter, which meant that they were responsible for shoveling snow off the hydrant after winter storms. The code for that application was placed in the Civic Commons and made available to others who went on to create Adopt-A-Siren for tsunami sirens in Honolulu, Adopt-A-Storm-Drain for clearing debris from storm drains in Seattle, and Adopt-A-Sidewalk also for snow removal in Chicago.

These are great examples of community engagement in improving public safety. Maybe we can one day return to a more positive image of public safety and policing, like Sheriff Taylor on Andy Griffith or Ponch and Jon on CHiPs – the images that I grew up with.

These are great examples of community engagement in improving public safety. Maybe we can one day return to a more positive image of public safety and policing, like Sheriff Taylor on Andy Griffith or Ponch and Jon on CHiPs – the images that I grew up with.

Feedback and more examples of citizen engagement in public safety and community policing are always welcome.