Microsoft’s European Fine Comes In An Era Of Browser Diversity

Today the European Commission fined Microsoft €561 million ($732 million) for failing to live up to a previous legal agreement. As the New York Times reported it, “the penalty Wednesday stemmed from an antitrust settlement in 2009 that called on Microsoft to give Windows users in Europe a choice of Web browsers, instead of pushing them to Microsoft’s Internet Explorer.” The original agreement stipulated that Microsoft would provide PC users a Browser Choice Screen (BCS) that would easily allow them to choose from a multitude of browsers.

Without commenting on the legalities involved (I’m not a lawyer), I think there are at least two interesting dimensions to this case. First, the transgression itself could have been avoided. Microsoft admitted this itself in a statement issued on July 17, 2012: “Due to a technical error, we missed delivering the BCS software to PCs that came with the service pack 1 update to Windows 7.” The company’s statement went on to say that “while we believed when we filed our most recent compliance report in December 2011 that we were distributing the BCS software to all relevant PCs as required, we learned recently that we’ve missed serving the BCS software to the roughly 28 million PCs running Windows 7 SP1.” Subsequently, today Microsoft took responsibility for the error. Clearly some execution issues around SP1 created a needless violation.

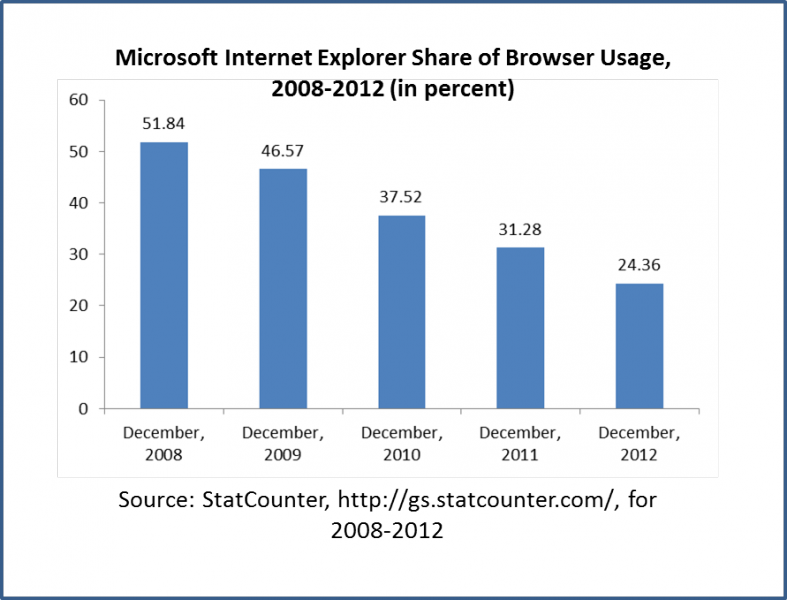

Second, and more interestingly, the browser environment looks very different today than it did in the mid-2000s (when the European Commission pursued its investigations) or in December, 2009 (when the EC and Microsoft reached their legal settlement). According to StatCounter – a web tracking site that samples more than 15 billion page views per month collected from across more than 3 million websites: Microsoft Internet Explorer traffic constituted 51.84% of European browser traffic in December, 2008, but only 24.36% in December, 2012.

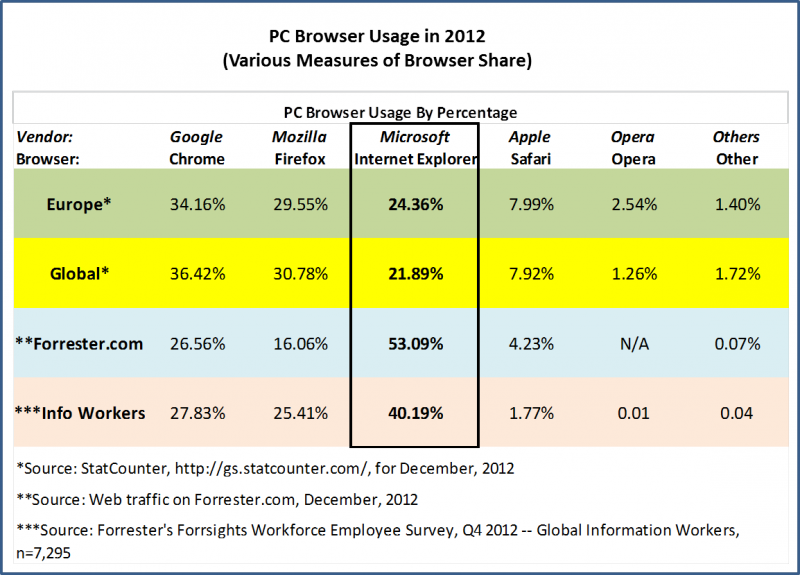

StatCounter’s isn’t the only method of measuring browser usage. But looking at a number of different measures, we see that we’re living in an era of browser diversity. While the StatCounter measures show Internet Explorer in third place (both globally and in Europe), two other sources show Internet Explorer in first – but heavily contested by Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox.

- Forrester.com’s own web traffic. This data skews toward business users accessing our site from their offices, and further skews toward Forrester’s client base. It yields the highest measure (53.09%) of IE usage but shows that usage is strongly contested by other browsers.

- Self-reported usage of information workers. While tracking actual web analytics can be powerful, the self-reported usage (in this case, by information workers in Forrester's Forrsights Workforce Employee Survey, Q4 2012) offers a different view. We asked IWs to tell us which browser they, personally, use most frequently, and 40.19% said it was Internet Explorer.

Why is the browser market now so fragmented? We’ll be exploring this issue in an upcoming report, but the reasons are legion. For enterprise (as opposed to pure consumer) usage, legacy business applications are often associated not just with Internet Explorer, but with specific versions (IE6, IE7, IE8, IE9). At the same time, certain public web sites (e.g. Google’s properties, with Chrome) might perform differently when accessed via different browsers. And bring-your-own (BYO) behavior by workers extends not just to devices, but also to browsers (e.g. installing multiple browsers outside the one “sanctioned by IT”) and to services (e.g. subscribing to Dropbox to help you do your job better).

Finally, I haven’t even mentioned mobility here. The data in this blog post comes from the normative PC/Mac laptop/desktop analytics. But the right way to think about this market is to combine PCs, tablets, and smartphones into a single computing market. (I haven’t done so here due to the contours of the European Commission case).

The bottom line is that browser diversity today has, by many measures, been achieved. In future posts and reports, we’ll discuss how much this matters to I&O professionals and what they should be doing about it.