Your Return-To-Office Policy Isn’t Working

Your return-to-office (RTO) policy isn’t working today, and it won’t ever work — at least, if by work, we mean a policy that satisfies the in-office preferences of the executive team without driving some of the best workers to distraction or worse. This is because the policy itself can’t accomplish anything without the hard work necessary to develop and implement an approach to enforcement that you can maintain. That’s honestly the part that leaders have put the least effort into, as we’ve written in our latest report, The Facts About Hybrid Work Policy In 2025. In the report, we evaluate the data available on hybrid work in the US from our own surveys of thousands of workers and decision-makers over the past decade as well as a review of the most robust data available from academic researchers at Stanford and elsewhere.

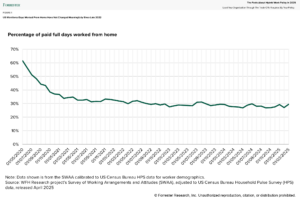

The facts make one thing clear: Most policies are not being complied with. On average, employees operating under hybrid work policies are given 2.1 days a week to work remote, a number that has fallen by a full day over the past few years. Yet even as the policies have tightened, the number of days that people actually work remote has not changed meaningfully since late 2022.

This means that as policies tighten, compliance is actually getting worse. We predict that in 2030 the number of days hybrid workers are in the office will have dropped by half a working day per week to 1.6 days total. Yet we predict actual days worked remote will not have dropped by the same amount.

For executives hidebound and determined to see more workers in the office more days per week, their gut response will be to reduce flexibility even more, cracking down on the people who are undermining what executives perceive as the extra productivity and culture energy they would have if only more people were in the office, believing that if some slackers are driven out of the organization, this will only allow the company to regroup around its core performers. Unfortunately for them — as we show clearly in our report — none of that is true. Productivity is not higher and, in some cases, it’s worse when people are compelled to work in the office. Culture energy is actually higher for people who have work flexibility, and according to a University of Pittsburgh analysis of more than 3 million tech and finance workers’ employment histories, people who attrit after hybrid work policy changes are among the highest-qualified and most senior performers.

None of this argues that your policy should change. Hopefully you made your decisions in light of the data we’ve been sharing for years that is now showing all of these things to be true. But it does argue that how you manage enforcement of your policy requires your thoughtful attention and careful leadership. In the report, we break out two broad approaches — loose enforcement and tight enforcement — and show how each can be done in a way that more effectively manages the risks and mitigates the consequences of your policy. Under tight enforcement, you face specific, measurable risks to which you can manage. Under loose enforcement, it’s harder to measure the short-term impact, but long-term metrics such as engagement and attrition favor you. Forrester clients can read the report to learn more.

My personal plea to leaders on this topic: Stop personalizing this policy. The numbers are in — some of your decisions are having a positive effect, and some are having a negative effect. If you aren’t measuring the effects that your policy is having and then responding with policy or enforcement adjustments that manage to those metrics, you are missing the opportunity to really lead. And you’re going to need to be that kind of leader to get your organization through all the volatility and uncertainty you currently face. It would be nice to go into those tough decisions having already shown that you know how to handle tough choices involving smart and good people who can genuinely disagree over policy and enforcement.