Trust Is The Killer App To Unlock AI Adoption

In the late 1960s, Joseph Weizenbaum, an MIT psychologist, developed ELIZA, a procedurally driven psychiatric chatbot. In response, Kenneth Colby of Stanford created PARRY, a model of a paranoid schizophrenic. The two connected online in 1972. Suffice to say, they didn’t get on. Their conversation (you can read the entire thing — it’s not pretty) neatly articulates one of the key questions we need to ask ourselves when we consider the development of new AI-powered customer experiences:

Ask Not “Can We?” But “Should We?”

Science fiction has wrestled with the question of human-created intelligence arguably since the days of the first work of science fiction, Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” Yet science fiction usually posits not “Can we?” or even “Should we?” … instead, it leaps straight to “We already did, and it all went horribly wrong.” Science fiction has already given us an elegant ethical framework to govern the development of artificial intelligence: Isaac Azimov’s three laws of robotics. Elegant and simple, yes. Science fiction? Maybe, or maybe not.

Robots are among us already, perhaps more than we realize, or at least more than many consumers realize, and our reactions to these seemingly benign assistants can be complex. The uncanny valley hypothesis predicts that an entity appearing almost human will risk eliciting eerie feelings in viewers in a way that obviously unhuman entities, such as Pepper the customer service robot or a robot arm in a factory, do not. The problem is that we’ve already surpassed the point of obviously unhuman:

- Lil Miquela has more than 2 million Instagram followers and pulls down 10 grand a day modeling for brands like BMW. But Lil Miquela is code. She’s one of a growing breed of virtual influencers, a virtual entity currently controlled by humans.

- The Velvet Sundown is a breakout Spotify success with more than a million monthly listeners. Not bad, given that they literally launched this year and are already releasing their third album. They, or perhaps it, is at the center of an ongoing controversy, as streaming platform Deezer has tagged them as “100% AI” while Spotify says nothing. And the “band” claims to be real … or do they?

AI Is Everywhere, But Who (Or What) Do You Trust?

Examples like Velvet Sundown highlight the difficulty we increasingly face in understanding where AI is being used.

- Consumers are confused. According to Forrester’s Consumer Benchmark Survey, 2025, 68% of Australian consumers think chatbots might be powered by AI, yet only 58% think that AI powers self-driving cars — which means that 42% of consumers don’t think that AI is driving self-driving cars. And in the UK, it’s even worse, yet some eight in 10 UK consumers agree that “companies should disclose where AI is being used.”

- Enterprises are concerned. AI is live in enterprises around the world. For customer experience use cases such as improving efficiency of customer-facing employees, identifying patterns in customer feedback and data, or analyzing contact center interactions, we now see some 30–40% of firms worldwide reporting production implementations. For the majority that aren’t there yet, the blockers aren’t technical. Ethics, privacy, and trust, along with employee experience and readiness, top the reasons why firms aren’t adopting generative AI.

Trust Is The Killer App To Drive AI Adoption

Emerging AI legislative approaches such as the EU AI Act or Australia’s emerging stance are risk- and principles-based. They lean into building trust through common principles like transparency, accountability, or fairness. Many of these principles are common across frameworks and map to the levers of trust in our own trust framework. We define trust as:

The confidence in the high probability that a person or organization will spark a specific positive outcome in a relationship.

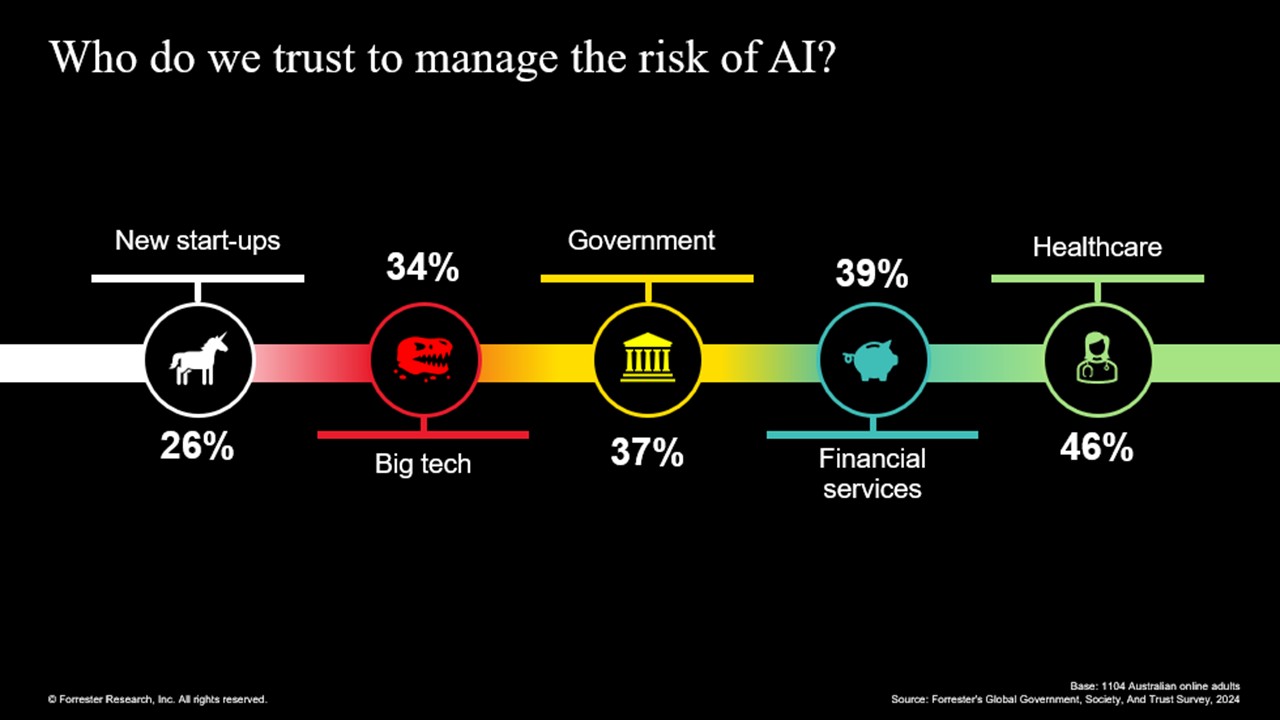

But who do we trust to manage the risks of AI? As you can see from the following graphic, consumers are far more likely to trust regulated businesses, such as banks, to deploy trustworthy AI than less strictly governed businesses, such as technology firms.

But don’t make the mistake of thinking that trust is nebulous or intangible. It’s hard won, easily lost, and highly measurable. Our latest research refreshes our trust framework and takes the AI risk levels outlined in the EU AI Act to examine how the drivers of trust change depending on consumer perception of risk. And the drivers do change. Consumers might be confused, but they definitely don’t want to be lied to.

If you want to learn more, we spoke about AI design principles on the CX Cast last year. If you are a Forrester client, check out our latest trust research or book a guidance session with myself or Enza Iannopollo.