What Technical Debt Means To IT Professionals

Technical debt continues to rise as a priority for IT leaders. While AI may be grabbing the front-page headlines, tech debt is lurking below the surface in more and more industry conversations. Ironically, for such a hot topic, there’s little consensus on how to even define it.

It’s No Longer Just Code

When Forrester’s Modern Technology Operations Survey, 2025, asked 593 IT professionals what technical debt means to them, the results were surprising. “Immature” code — Ward Cunningham’s original definition and the focus of countless academic papers and LinkedIn commentaries — ranked low, with only 27% of respondents selecting it.

This data reveals a fundamental disconnect between how purists and academics define technical debt and how practitioners experience it. While some continue to insist that technical debt refers exclusively to shortcuts taken when writing software, IT practitioners clearly embrace a far broader definition.

It’s unsurprising: The word “technical” carries broad connotations, and thus real-world practitioners have naturally extended “technical debt” to encompass all deferred technical investment. When your most experienced engineers retire without documenting critical systems, you’re still critically dependent on Java 8, or your hardware could fail at any moment, these aren’t separate categories of debt that need distinct terminology. They’re all part of the technical debt burden that organizations must actively manage.

Managing The Full Portfolio

These aren’t isolated problems; as I’ve written elsewhere, they’re part of an integrated system of feedback loops. Sprawling, outdated tech requires outdated skills, increasing staff cognitive load and diluting focus. Inflexible architectures force organizations to build redundant systems rather than adapt existing ones. Incidents drive shortcuts drive more incidents. And so it goes.

Some argue for separate terminology: infrastructure debt, architecture debt, process debt. But this misses the point. Organizations need an umbrella term for deferred technical work and investment. Don’t confuse your leaders and business partners with multiple terms and flavors. Keep it simple, and you’re more likely to get the resources you need.

The Path Forward

Forrester data provides clear guidance on where organizations should focus.

- Knowledge and process debt, selected by 37% of respondents, demands immediate attention through process improvement, reengineering, and organizational change management.

- Unsupported vendor software and redundant IT systems, each selected by 30–32% of respondents, require proactive migration planning before crisis points emerge.

- System inflexibility, identified by 35%, calls for architectural investments in future options.

- And yes, code quality, selected by 27%, deserves attention as part of the portfolio but not as the sole focus.

For academics and purists insisting that a Ward Cunningham-derived definition is a strict scope:* It’s time to acknowledge that language evolves based on utility, not theoretical purity, and the horse has left the barn. Fighting this evolution wastes energy that could be spent developing better frameworks for managing the full spectrum of technical obligations.

For practitioners, the message is validating: You’re not wrong to call all of this technical debt. Your daily reality of managing everything from knowledge gaps to hardware failures under a single conceptual umbrella makes operational sense. The interconnected nature of these challenges demands integrated management, not artificial separation.

For organizations, the path forward is clear. Stop letting terminology debates distract from the real issue. You have a portfolio of deferred technical investment that requires active management and ongoing investment (the emerging best practice is that 20–25% of ongoing spend be devoted to modernization). Some involves code, much doesn’t, and all of it compounds over time.

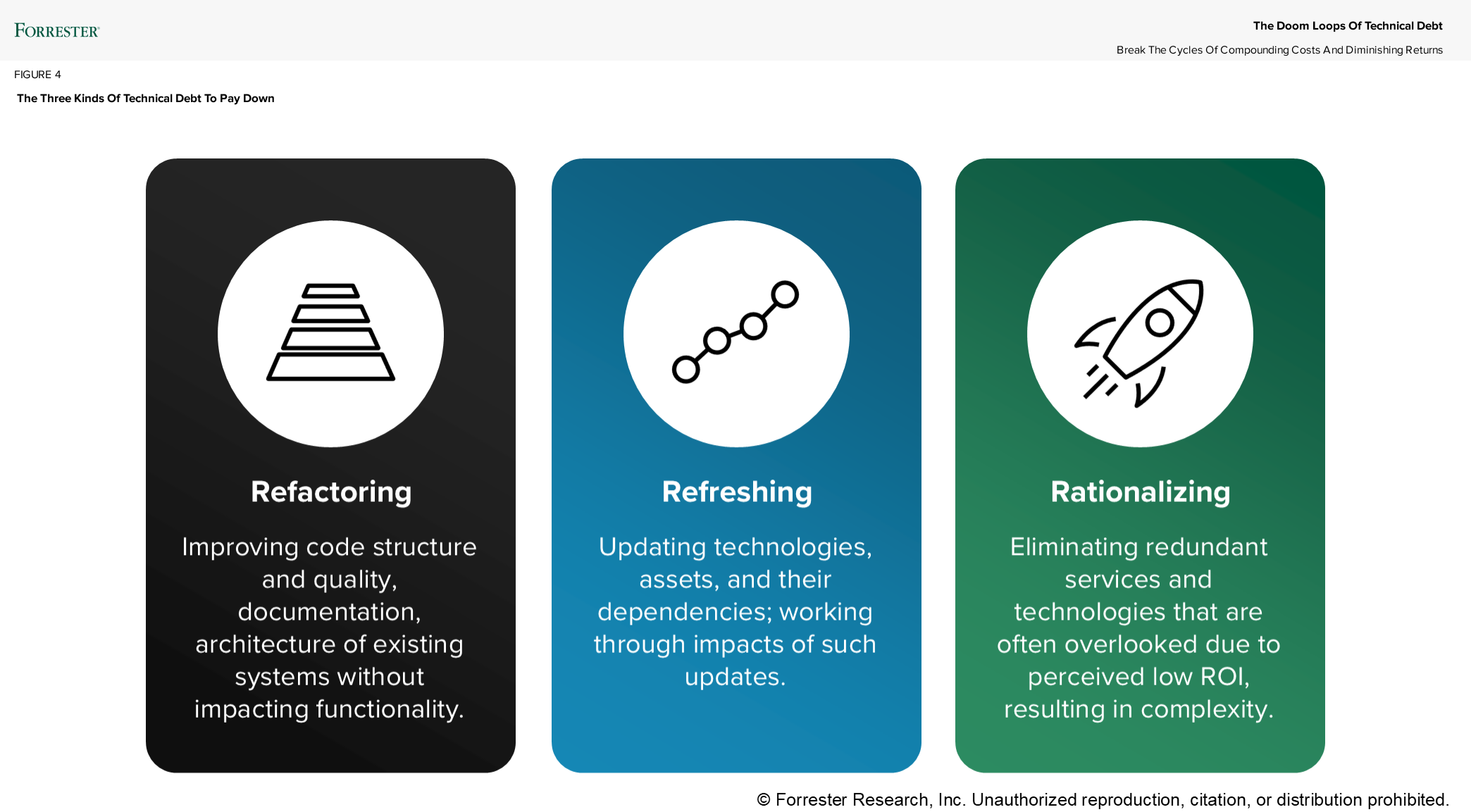

The question isn’t what to call these different types of deferred work — practitioners have already decided. The question is how to manage them effectively as the interconnected portfolio of nonoptional spending they’ve always represented. We propose three major levers: refactoring, refreshing, and rationalizing.

Practitioners know exactly what their technical debt encompasses in their complex digital operations. The most successful organizations will embrace this broader understanding and develop portfolio management strategies that address technical debt in all its forms — from the knowledge walking out the door, to systems that can’t adapt, to sprawl and obsolescence, and to the code that, yes, could be cleaner.

In an era when IT underpins every aspect of business success, managing technical debt as a comprehensive portfolio isn’t just good practice — it’s essential for survival. The 593 professionals surveyed by Forrester aren’t confused about terminology. They’re dealing with reality. It’s time the purists and academics catch up.

Let’s continue the conversation: Request a guidance session.

*One major difference between the current academic writings and operational reality – even the most current definition (the “Dagstuhl consensus”) focuses on “constructs that are expedient in the short term.” This overlooks the fact that perfectly reasonable decisions and fully matured architectures inevitably age, and debt emerges organically in the portfolio.