“CMDB” Is Dead — Long Live The IT Management Graph

A couple weeks ago at Forrester’s Technology & Innovation Summit EMEA in London, I declared the configuration management database (CMDB) to be dead. I don’t usually indulge in “X is dead” clickbait, but the term “configuration management database” has caused decades of confusion.

Let me be very clear: Whenever you have a large-scale organizational capability, you’re going to have an information management problem, and so we have a big information management problem in managing large-scale digital and IT estates.

But the CMDB term continues to hinder our progress.

A Misguided Legacy

I trace the CMDB’s roots back to ITIL v1 in 1990, and this guidance in turn borrowed heavily from military and aerospace configuration management. That heritage was ill suited to the dynamic, distributed, software-driven evolution of IT. Worse, the name itself — “configuration management database” — implied it was a repository that could store “configurations” in the general case. It couldn’t — not in 1990, not now.

The misnomer drove impossible expectations. I saw this firsthand in banking, where auditors assumed that CMDB ownership meant responsibility for Unix server hardening and executives asked whether it was the right place to control low-level network card settings. It took years (and even an intervention into COBIT) to correct such misconceptions.

At Forrester we call this “element configuration management” and the right tools were (at the time) products like BladeLogic and Opsware, and, later, infrastructure as code products like Puppet, Chef, and Ansible.* Some might call me out for going back in history here, but CMDB as an idea is still propagating worldwide and being adopted by companies as they scale, and these misunderstandings continue. I hear them firsthand.

The CMDB was never designed to manage low-level configuration parameters — too numerous and too volatile, with ever-changing schemas, nor did the CMDB ever have the power to actually change those settings. Yet organizations still buy discovery tools, crank them (ala Spinal Tap) to eleven, fill their CMDBs with stale low-level data, and wonder why engineers ignore it. Pro tip: When troubleshooting, sysadmins don’t consult cached values in a database; they SSH into the device for real-time truth.

The Real Value — And The Real Problem

Once you accept this limitation, you will still find the CMDB necessary for large scale digital estates. It’s your basic inventory set (starting with IT asset management.) Beyond that, it can provide context via tracking dependencies – impacts, relationships, etc.. You can’t figure out much about the device’s business purpose — e.g., who owns its workloads, or even who’s on call — from an SSH session.

Tracing low-level resources up to support staff and business impact is where the CMDB has a unique role. But for these purposes, the term “configuration” is a confusing stretch and leads to lack of clarity about the true nature of the problem: data management.

This is the heart of the issue: CMDBs were in most cases built and managed by ITIL/ITSM process experts, not data managers. ITIL’s original military-spec terminology (“configuration item identification, configuration status accounting”) never aligned with industry-standard data practices (“schema design, data quality reporting”). The result? Poor modeling, weak governance, process confusion, and silly debates (“Is a person a CI?”). Without solid data management practices, many CMDBs collapsed under their own weight. Dependency data is expensive and hard to manage.

When leaders ask me why their CMDB efforts are failing — often after three or four attempts — my usual finding is simple: They haven’t involved anyone with real data management expertise. The CMDB was a product of IT service management, a process-centric framework. Data management is a different discipline entirely, governed by the Data Management Association and the Data Management Body of Knowledge. Few practitioners are deep in both.

The Graph Awakens

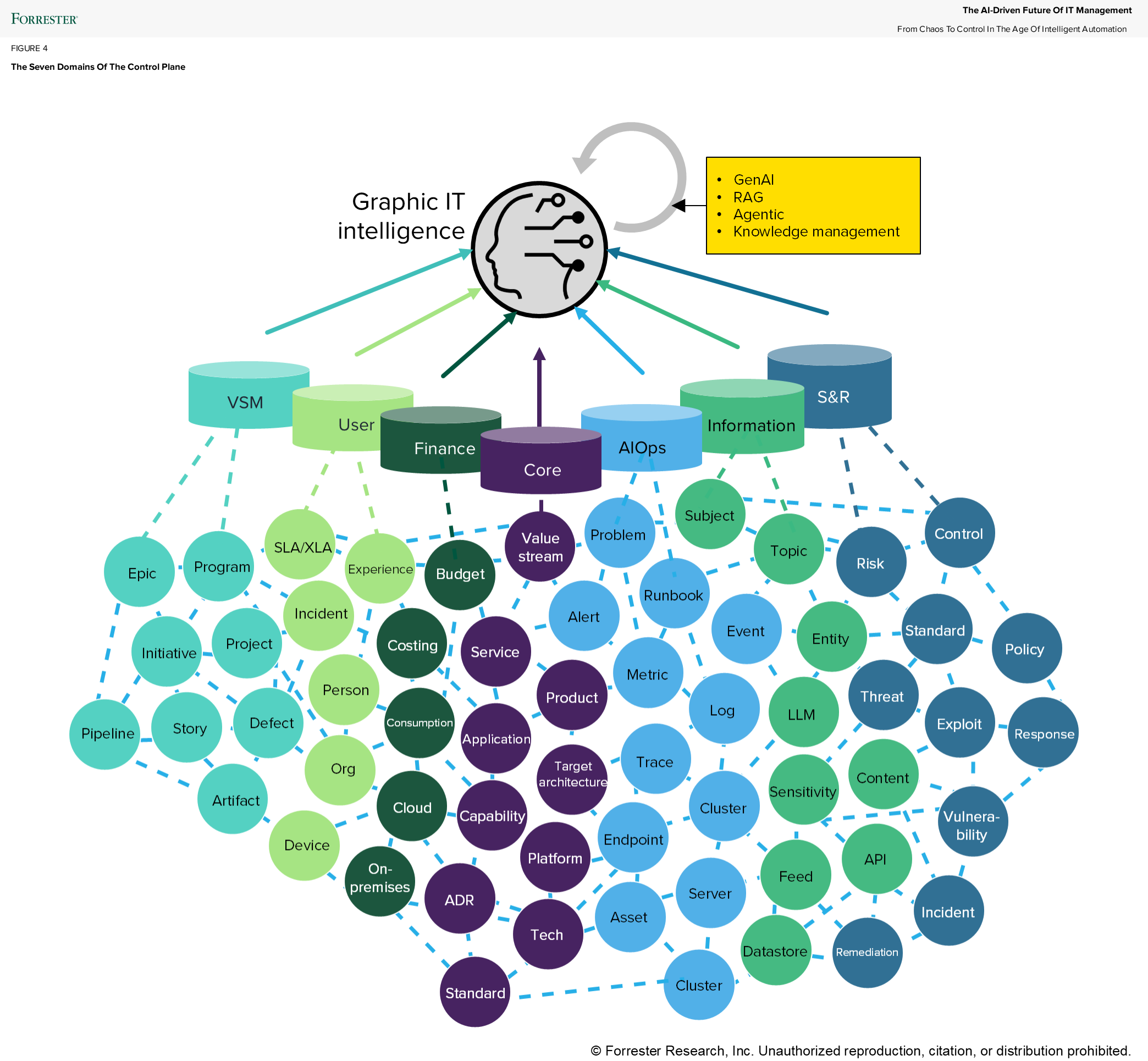

For years, we searched for better terminology: “business of IT data,” “IT data management platform,” and so on. ITIL v3 itself proposed “configuration management system,” which didn’t resolve the fundamental confusion with the term “configuration.” But now, we have a viable alternative: the IT management graph.

Graph databases have existed for years, but the rise of generative AI and graph RAG has brought them to the forefront for IT management. Vendors such as Atlassian, ServiceNow, Dynatrace, Flexera, and Planview now lead with graph-centric messaging. At recent conferences and briefings, “graph” is dominating the narrative while “CMDB” is fading.

The graph model fits IT management data perfectly. This data is not particularly voluminous (aside from logs, which again don’t belong in the CMDB), but it’s deeply interconnected. Multi-hop transitive dependencies are the norm. To understand exposure, impact (i.e., blast radius), and lineage, from technical resources to business capabilities, you need a graph.

So at Forrester, we’re deprecating the term CMDB. In our research, you’ll increasingly see it termed “IT management graph.”

Toward Quality And Maturity

Will the data in these graphs be perfect? No. But perfection isn’t the goal — fit-for-purpose is. Data governance, exception reporting, continuous improvement are key. We’re seeing a quality revolution, driven by:

- Agents that assist with data curation.

- OpenTelemetry for dependency insight.

- Extended Berkeley Packet Filter-based telemetry.

- Integrations with increasingly intelligent observability tools (the Dynatrace adapter into the ServiceNow graph is one of the most popular)

ServiceNow is already operationalizing data quality reporting and I call on everyone else in this space to do the same.

Final thoughts

Why did we keep banging our head against the wall, trying to build CMDBs despite repeated failures? Because we had no choice. IT consumes 3% of corporate budgets and underpins most revenue. Regulations like HIPAA, DORA, and GDPR demand visibility. We’ve got to know what we have and how it connects.

We will continue to need robust information management, and as we finally get it, we are going to be able to solve increasingly challenging problems in digital and IT management, such as technical debt.

Now, with graphs, we’re finally getting there. It’s time to leave the past behind and embrace a mature, data-centric future.

Long live the IT management graph.

Want to discuss? Join me at Forrester’s Technology & Innovation Summit North America (November 2–5, 2025, in Austin, Texas, and digitally) to learn more about the IT management graph and why it’s important. Forrester clients can access our exclusive reports and schedule a guidance session to explore current trends and solutions.

PS. At the risk of making this overly long, I want to share another example of the power of terminology and how decisions made years ago can linger, creating friction across the industry.

When the Scrum framework was first introduced, its creators coined the term “Product Owner”: a relatively tactical role—someone responsible for managing the backlog. But the word “owner” carries weight. It implies authority and seniority.

Fast forward to today’s product-centric operating models, and we see an odd inversion: Product Owners often report to Product Managers. When executives glance at an org chart, they scratch their heads—after all, “owner” sounds more senior than “manager.” This mismatch has persisted, with much ongoing industry controversy. Product thought leader Marty Cagan states “The rise of product owners has done more damage to the craft of product than anything else I can think of in the past 40 years” and calls for its sunset. Yet the Scrum community continues to hold firm to its original definition, leaving us with another case of terminological confusion that destroys value.

The point is simple: language matters, and sometimes terminology needs to be challenged and retired. As an industry analyst, part of my job is to surface these issues and contribute to the conversation. I don’t think genAI will play that role any time soon….

*BladeLogic and Opsware were acquired by BMC and HP, respectively. Progress Software bought Chef and Perforce bought Puppet. And of course much of element config is now handled automatically with Docker and Kubernetes.