Can You See Me Now? New Observability Reports!

The time has come to complement my AIOps Reference Architecture with an Observability Reference Architecture of its own. Anyone that has met and spoken with me since joining Forrester last year knows that I see the two topics as separate but genetically joined. That research has resulted in two new reports that focus exclusively on observability — the latest “best thing since sliced bread.” My hope is to help clarify what it is and how to move forward with observability. These are the first two in what is likely to be a long series of reports on observability.

Confusion and misunderstanding about observability are rampant right now, which is no good for anyone, so step one is to put a stake in the ground on a definition for “observability”:

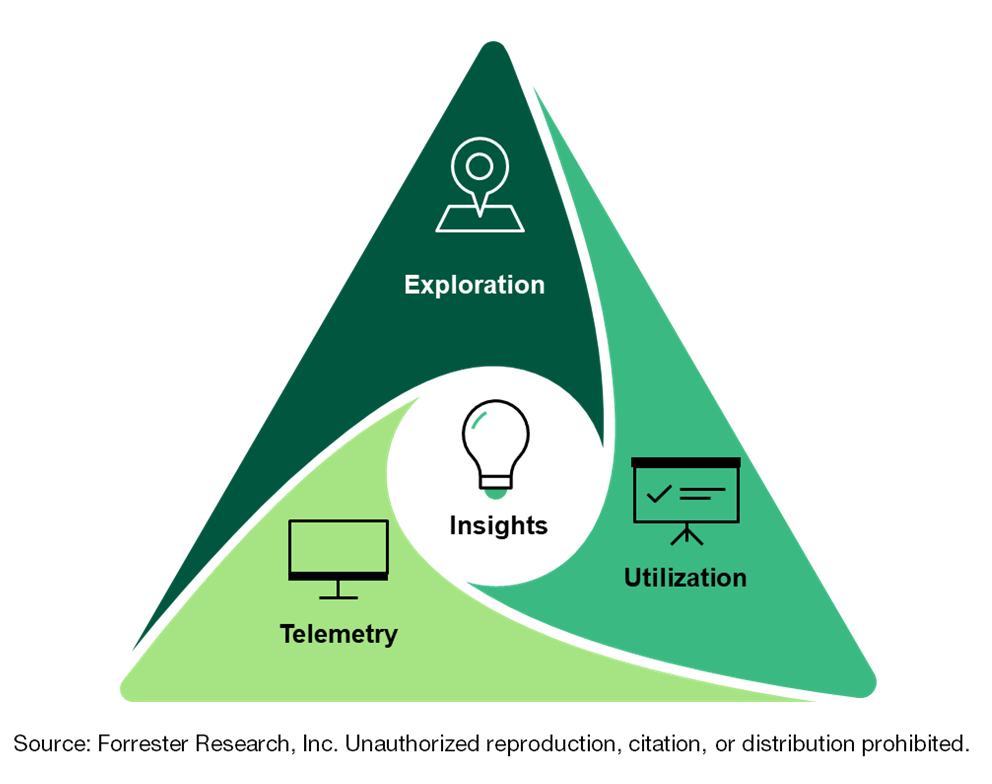

An inherent ability of an entity to allow exploration and analysis through immutable externalized outputs. Exploration of its characteristics and behavioral patterns provides real-time visibility; real-time and historical analysis interprets and infers the internal state and operations to provide insights and actionable information.

Observability Reference Architecture

The first report introduces the Forrester Observability Reference Architecture. A big thank you goes out to Naveen Chhabra, my partner in crime on observability, for his invaluable guidance and insights to help bring this to fruition. It’s important to remember that a reference architecture is not detailed with a strategic map. The Observability Reference Architecture lays out four core areas of functionality/capability (telemetry, exploration, insights, and utilization) as a basis for discussing how to operate a system in the most efficient and resilient manner. Remember that your observations must be actionable; otherwise, they’re a waste of time. That’s why utilization is so important but often flies under the radar in observability discussions.

The intention of and expectation for this reference architecture is for it to become a common starting point for discussions about observability. The concept of observability is not currently founded on a lot of set or accepted principles. Therefore, conversations about observability tend to meander everywhere from detailed monitoring to broad and common operational efforts. Worse — and a pet peeve of mine — is that the term is cropping up in everything under the sun now that marketing departments have gotten a hold of it. We need to collectively get ahead of this, even though the word itself is fundamentally a challenge. Is it a noun, a verb, or an adjective? I’ll hold off on that for now but will revisit it soon.

What’s A Picture If You Don’t Know What To Do With It?

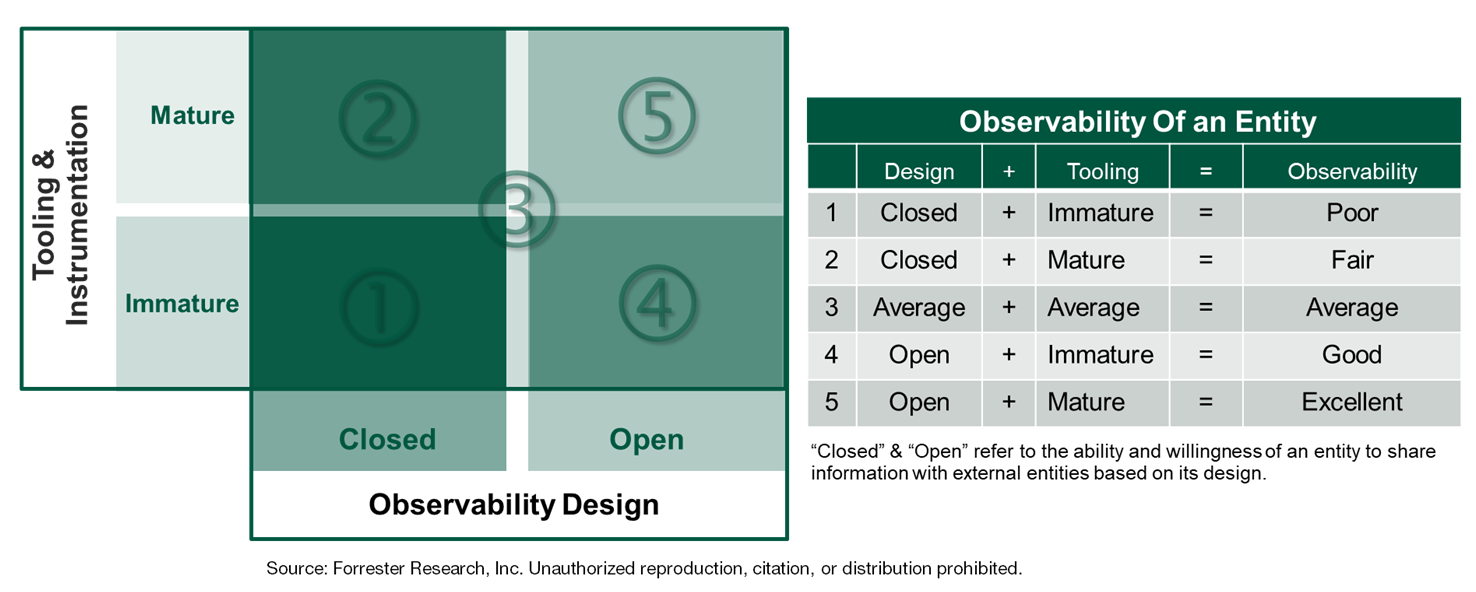

Reference architectures are meaningless if you don’t know what to do with them or how to apply them. That’s where the second report comes into place. The Forrester Observability Reference Architecture: Putting It Into Practice report speaks to how shared responsibilities enable observable insights. It provides some guidance on the sorts of things that Naveen Chhabra and I wrote about in previous blogs on observability. It reiterates that the entity you’re trying to observe must be willing to be observed; therefore, it has to be designed in a manner so that it can be observed. Secondly, for observability to materialize, the tooling and instrumentation must be able to observe it. Naveen uses the example of radar and stealth aircraft to make this point. In the case of observability, the radar may not be able to detect the stealth aircraft because the aircraft was deliberately designed to not be observed — aka, the aircraft is not willing to be observed.

This means there are two core elements that enable or prohibit observability: observability design and tooling/instrumentation. Weaknesses in either, or deliberate prohibitions in design, will limit the extent to which observability is possible. It’s important to understand that design will always be the limiting factor on observability. Think of it in a security sense or in the case of Naveen’s stealth aircraft example. Some devices on our networks are far more critical to our success, so we don’t want them to be “observed in action.” Therefore, we deliberately design them to share very little detail about how they operate, what’s going on “inside the box” or, in some cases, that they even exist. In these cases, no matter how good your tooling and instrumentation is, your ability to observe the device is limited by the entity’s design and willingness to be observed. Below is a variation of the graphic in my report to help you grasp the idea.

What’s Next, And Where Do You Begin?

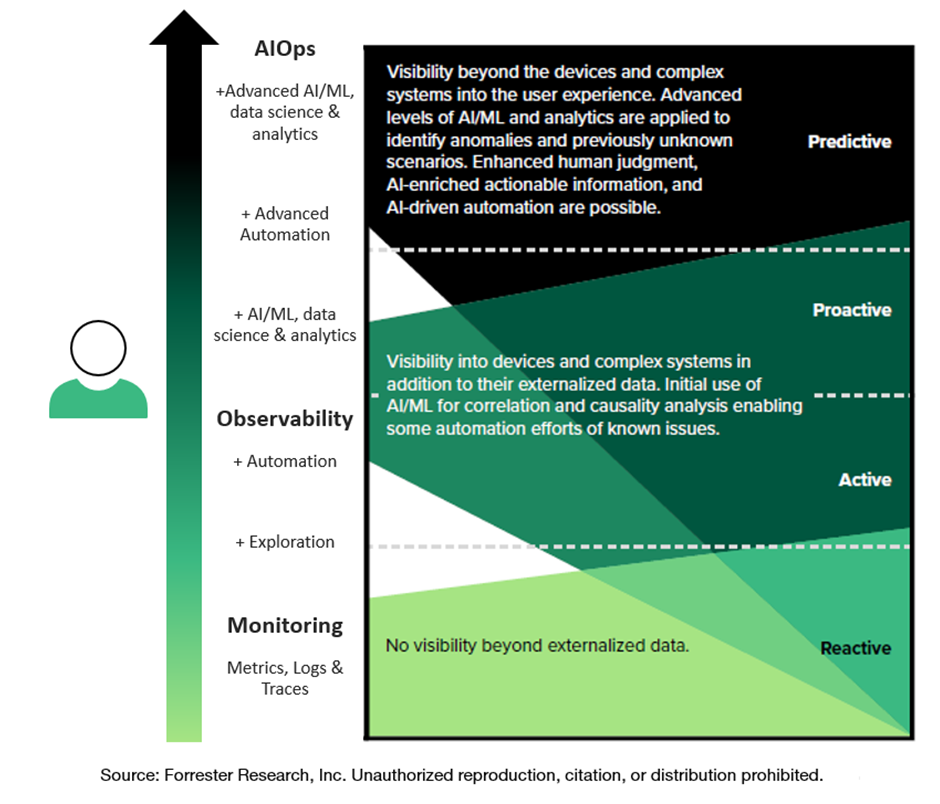

We are experiencing a period of extreme changes at incredible speeds. If you’re debating on waiting it out for things to settle down, rest assured that it won’t happen and you will be left behind wondering how you are so far behind your peers. The first step you need to take is to understand the difference between monitoring, observability and AIOps. Unfortunately, the terms are often used interchangeably due to a lack of understanding. That is causing lots of efforts to fail, mostly due to wrong expectations. Below is an image that demonstrates the genetic relationship between these topics.

You can’t separate these three important topics, but you must understand their unique capabilities so that you can tackle each tactically to move in a direction that is strategically aligned with your corporate goals. Get acquainted with the differences and get moving on your journey, because your peers have.

Join The Conversation

I invite you to reach out to me through social media if you want to provide general feedback. If you prefer more formal or private discussions, email inquiry@forrester.com to set up a meeting! Click Carlos at Forrester.com to follow my research and continue the discussion.